Why the Economic Fates of America’s Cities Diverged

Places like St. Louis and New York City were once similarly prosperous. Then, 30 years ago, the United States turned its back on the policies that had been encouraging parity.

Despite all the attention focused these days on the fortunes of the “1 percent,” debates over inequality still tend to ignore one of its most politically destabilizing and economically destructive forms. This is the growing, and historically unprecedented, economic divide that has emerged in recent decades among the different regions of the United States.

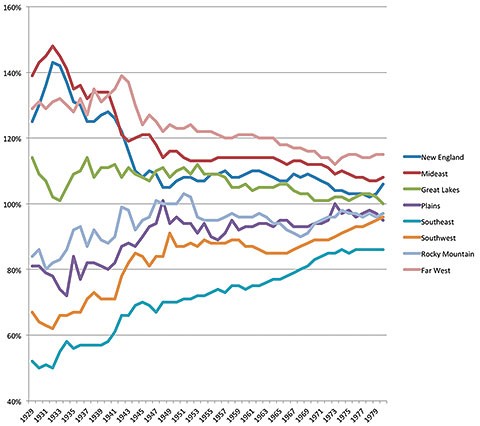

Until the early 1980s, a long-running feature of American history was the gradual convergence of income across regions. The trend goes back to at least the 1840s, but grew particularly strong during the middle decades of the 20th century. This was, in part, a result of the South catching up with the North in its economic development. As late as 1940, per-capita income in Mississippi, for example, was still less than one-quarter that of Connecticut. Over the next 40 years, Mississippians saw their incomes rise much faster than did residents of Connecticut, until by 1980 the gap in income had shrunk to 58 percent.

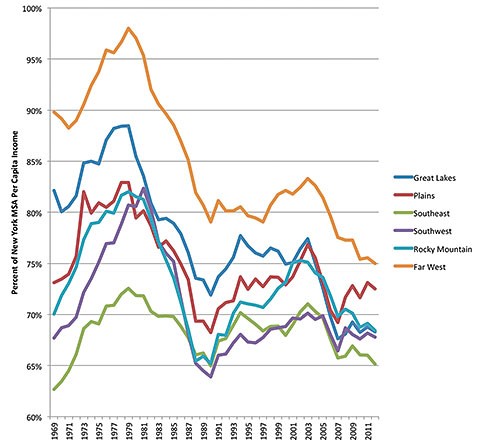

Yet the decline in regional equality wasn’t just about the rise of the “New South.” It also reflected the rising standard of living across the Midwest and Mountain West—or the vast territory now known dismissively in some quarters as “flyover states.” In 1966, the average per-capita income of greater Cedar Rapids, Iowa, was only $87 less than that of New York City and its suburbs. Ranked among the country’s top 25 richest metro areas in the mid-1960s were Rockford, Illinois; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Ann Arbor, Michigan; Des Moines, Iowa; and Cleveland, Ohio.

During this period, to be sure, many specific metro areas saw increases in local inequality, as many working- and middle-class families, as well as businesses, fled inner-city neighborhoods for fast-expanding suburbs. Yet in their standards of living, metro regions as a whole, along with states as a whole, were growing much more similar. According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, in 1940, Missourians earned only 62 percent as much as Californians; by 1980 they earned 80 percent as much. In 1969, per capita income in the St. Louis metro area was 83 percent as high as in the New York metro area; it would rise to 90 percent by the end of the 1970s.

The rise of the broad American middle class in that era was largely a story of incomes converging across regions to the point that people commonly and appropriately spoke of a single American standard of living. This regional convergence of income was also a major reason why national measures of income inequality dropped sharply during this period. All told, according to the Harvard economists Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag, approximately 30 percent of the increase in hourly-wage equality that occurred in the United States between 1940 and 1980 was the result of the convergence in wage income among the different states.

Few forecasters expected this trend to reverse, since it seemed consistent with the well-established direction of both the economy and technology. With the growth of the service sector, it seemed reasonable to expect that a region’s geographical features, such as its proximity to natural resources and navigable waters, would matter less and less to how well or how poorly it performed economically. Similarly, many observers presumed that the Internet and other digital technologies would be inherently decentralizing in their economic effects. Not only was it possible to write code just as easily in a treehouse in Oregon as in an office building in a major city, but the information revolution would also make it much easier to conduct any kind of business from anywhere. Futurists proclaimed “the death of distance.”

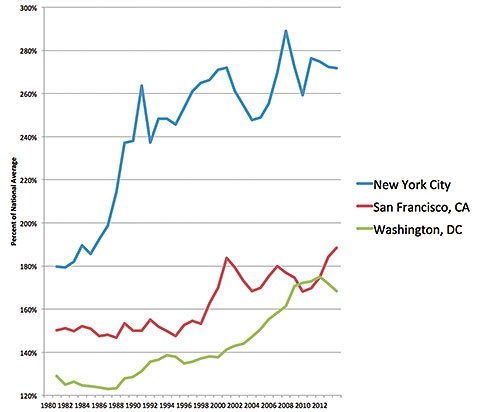

Yet starting in the early 1980s, the long trend toward regional equality abruptly switched. Since then, geography has come roaring back as a determinant of economic fortune, as a few elite cities have surged ahead of the rest of the country in their wealth and income. In 1980, the per-capita income of Washington, D.C., was 29 percent above the average for Americans as a whole; by 2013 it had risen to 68 percent above. In the San Francisco Bay area, the rise was from 50 percent above to 88 percent. Meanwhile, per-capita income in New York City soared from 80 percent above the national average in 1980 to 172 percent above in 2013.

Adding to the anomaly is a historic reversal in the patterns of migration within the United States. Throughout almost all of the nation’s history, Americans tended to move from places where wages were lower to places where wages were higher. Horace Greeley’s advice to “Go West, young man” finds validation, for example, in historical data showing that per-capita income was higher in America’s emerging frontier cities, such as Chicago in the 1850s or Denver in 1880s, than back east.

But over the last generation this trend, too, has reversed. Since 1980, the states and metro areas with the highest and fastest-growing per capita incomes have generally seen hardly, if any, net domestic in-migration, and in many notable examples have seen more people move away to other parts of the country than move in. Today, the preponderance of domestic migration is from areas with high and rapidly growing incomes to relatively poorer areas where incomes are growing at a slower pace, if at all.

What accounts for these anomalous and unpredicted trends? The first explanation many people cite is the decline of the Rust Belt, and certainly that played a role. According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, in 1978, per capita income in metro Detroit was virtually identical to that in the metro New York area. Today, metro New York’s per-capita income is 38 percent higher than metro Detroit’s. But deindustrialization doesn’t explain why even in the Sunbelt, where many manufacturing jobs have relocated from the North, and where population and local GDP have boomed since the 1970s, per-capita income continues to fall farther and farther behind that of America’s elite coastal cities.

The Atlanta metro area is a notable example of a “thriving” place where per capita income has nonetheless fallen farther and farther behind that of cities like Washington, New York, and San Francisco. So is metro Houston. Per-capita income in metro Houston was 1 percent above metro New York’s in 1980. But despite the so-called “Texas miracle,” Houston’s per-capita income fell to 15 percent below New York’s by 2011 and even at the height of the oil boom in 2013 remained at 12 percent below. It’s largely the same story in the Mountain West, including in some of its most “booming” cities. Metro Salt Lake City, for example, has seen its per capita income fall well behind that of New York since 2001.

The Emergence of a Single American Standard of Living: Regional Per Capita Income as a Percentage of the National Average

Another conventional explanation is that the decline of Heartland cities reflects the growing importance of high-end services and rarified consumption. The theory goes that members of the so-called creative class—professionals in varied fields, such as science, engineering, technology, the arts and media, health care, and finance—want to live in areas that offer upscale amenities, and cities such as St. Louis or Cleveland just don’t have them.

But this explanation also only goes so far. Into the 1970s, anyone who wanted to shop at Barnes & Noble or Saks Fifth Avenue had to go to Manhattan. Anyone who wanted to read The New York Times had to live in New York City or its close-in suburbs. Generally, high-end goods and services—ranging from imported cars and stereos to gourmet coffee, fresh seafood, designer clothes, and ethnic cuisine—could be found in only a few elite quarters of a few elite cities. But today, these items are available in suburban malls across the country, and many can be delivered by Amazon overnight. Shopping is less and less of a reason to live in a place like Manhattan, let alone Seattle.

Another explanation for the increase in regional inequality is that it reflects the growing demand for “innovation.” A prominent example of this line of thinking comes from the Berkeley economist Enrico Moretti, whose 2012 book, The New Geography of Jobs, explains the increase in regional inequality as the result of two new supposed mega-trends: markets offering far higher rewards to “innovation,” and innovative people increasingly needing and preferring each other’s company.

“Being around smart people makes us smarter and more innovative,” notes Moretti. “Thus, once a city attracts some innovative workers and innovative companies, its economy changes in ways that make it even more attractive to other innovators. In the end, this is what is causing the Great Divergence among American communities, as some cities experience an increasing concentration of good jobs, talent, and investment, and others are in free fall.”

Yet while it is certainly true that innovative people often need and value each other’s company, it is not at all clear why this would be any more true today than it has always been. Indeed, programmers working on the same project often are not even in the same time zone. The same digital technology similarly allows most academics to spend more time emailing and Skyping with colleagues around the planet than they do meeting in person with colleagues on the same campus. Major media, publishing, advertising, and public-relations firms are more concentrated in New York than ever, but there is no purely technological reason why this is necessary. If anything, digital technology should be dispersing innovators and members of the creative class, just as futurists in the 1970s predicted it would.

What, then, is the missing piece? A major factor that has not received sufficient attention is the role of public policy. Throughout most of the country’s history, American government at all levels has pursued policies designed to preserve local control of businesses and to check the tendency of a few dominant cities to monopolize power over the rest of the country. These efforts moved to the federal level beginning in the late 19th century and reached a climax of enforcement in the 1960s and ’70s. Yet starting shortly thereafter, each of these policy levers were flipped, one after the other, in the opposite direction, usually in the guise of “deregulation.” Understanding this history, largely forgotten today, is essential to turning the problem of inequality around.

Starting with the country’s founding, government policy worked to ensure that specific towns, cities, and regions would not gain an unwarranted competitive advantage. The very structure of the U.S. Senate reflects a compromise among the Founders meant to balance the power of densely and sparsely populated states. Similarly, the Founders, understanding that private enterprise would not by itself provide broadly distributed postal service (because of the high cost of delivering mail to smaller towns and far-flung cities), wrote into the Constitution that a government monopoly would take on the challenge of providing the necessary cross-subsidization.

Throughout most of the 19th century and much of the 20th, generations of Americans similarly struggled with how to keep railroads from engaging in price discrimination against specific areas or otherwise favoring one town or region over another. Many states set up their own bureaucracies to regulate railroad fares—“to the end,” as the head of the Texas Railroad Commission put it, “that our producers, manufacturers, and merchants may be placed on an equal footing with their rivals in other states.” In 1887, the federal government took over the task of regulating railroad rates with the creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission. Railroads came to be regulated much as telegraph, telephone, and power companies would be—as natural monopolies that were allowed to remain in private hands and earn a profit, but only if they did not engage in pricing or service patterns that would add significantly to the competitive advantage of some regions over others.

Passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890 was another watershed moment in the use of public policy to limit regional inequality. The antitrust movement that sprung up during the Populist and Progressive era was very much about checking regional concentrations of wealth and power. Across the Midwest, hard-pressed farmers formed the “Granger” movement and demanded protection from eastern monopolists controlling railroads, wholesale-grain distribution, and the country’s manufacturing base. The South in this era was also, in the words of the historian C. Vann Woodward, in a “revolt against the East” and its attempts to impose a “colonial economy.”

Running for president in 1912, Woodrow Wilson explicitly evoked the connection between fear of monopoly and fear of economic domination by distant money centers that had long dominated populist and progressive American politics. A month before the election, Wilson addressed supporters in Lincoln, Nebraska, asking,

Which do you want? Do you want to live in a town patronized by some great combination of capitalists who pick it out as a suitable place to plant their industry and draw you into their employment? Or do you want to see your sons and your brothers and your husbands build up business for themselves under the protection of laws which make it impossible for any giant, however big, to crush them and put them out of business, so that they can match their wits here, in the midst of a free country with any captain of industry or merchant of finance … anywhere in the world?

After winning the election, Wilson set out to implement his vision, and that of his intellectual mentor, Louis Brandeis, of an America in which the federal government used expanded political powers to structure markets in ways that maximized local control of local business. The Wilson-Brandeis program included, for example, passing the Clayton Antitrust Act, which targeted even incipient monopolies in the name of making the world safe for small business. It also included dramatic cuts in tariffs, which at the time were widely seen as propping up Northern manufacturing monopolies at the expense of the rest of the country.

It also included the establishment of the Federal Reserve System, which aimed to shift control of finance and monetary policy from private bankers in New York to a transparent public board, with voting power dispersed across 12 member banks headquartered in cities across the Heartland such as St. Louis, Minneapolis, and Kansas City. In the Wilson-Brandeis vision, effective government management of the economy meant maintaining equality of opportunity not only among firms but also among the different regions of the country.

These and similar public measures enacted early in the 20th century helped to contain the forces pushing toward greater regional concentrations of wealth and power that inevitably occurred as the country industrialized. Standard Oil sucked wealth out of the oil fields of western Pennsylvania, and transferred it to its headquarters in New York City, for example, but the government broke up the colossus into 34 regional companies, ensuring that the oil wealth was widely shared geographically.

Working toward the same end were laws, mostly enacted in the 1920s and ’30s, that were explicitly designed to protect small-scale retailers from displacement by chain stores headquartered in distant cities. Indiana passed the first of many graduated state taxes on retail chains in 1929. In 1936, overwhelming majorities in the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate joined in by passing federal anti-chain-store legislation known as the Robinson-Patman Act.

Sometimes referred to by its supporters as “the Magna Carta of Small Business,” Robinson-Patman prevented the formation of chain stores even remotely approaching the scale and power of today’s Walmart or Amazon by cracking down on such practices as selling items below cost (a practice known as “loss leading”). The legislation also prohibited the chains from using their market power to extract price concessions from their suppliers. Similarly, the Miller-Tydings Act, enacted by Congress in 1937, put a floor on retail discounting, thereby ensuring that large chains headquartered in distant cities didn’t come to dominate the economies of local communities. This did not prevent innovation in retailing, such as the emergence of brand-new supermarkets to replace small-scale butcher shops and green grocers. But into the 1960s, these and similar laws would ensure that no supermarket chain would control more than about 7 percent of any local market.

Another powerful policy lever used to limit economic concentration attacked patent monopolies. Starting in his second term in office, Franklin Delano Roosevelt dramatically stepped up antitrust enforcement, including by repeatedly forcing America’s largest corporations to license many of their most valuable patents. This policy took the form of consent decrees that, for example, resulted in General Electric having to license the patents on its lightbulbs, and, perhaps most consequentially, in AT&T having to share its transistor technology, which became the basis for the digital revolution.

In 1950, Congress significantly strengthened antitrust laws again by passing the Celler-Kefauver Act. In explaining the need for such legislation, Representative Emanuel Celler emphasized its effect on the regional distribution of wealth and power, noting that “the swallowing up of … small-business entities transfers control from small communities to a few cities where large companies control local destinies. Local people lose their power to control their own local economic affairs. Local matters are within remote control.”

Or, as Senator Hubert Humphrey put it in a debate on the Senate floor in 1952, “We are talking about the kind of America we want. … Do we want an America where the economic marketplace is filled with a few Frankensteins and giants? Or do we want an America where there are thousands upon thousands of small entrepreneurs, independent businessmen, and landholders who can stand on their own feet and talk back to their government or to anyone else?”

By the 1960s, antitrust enforcement grew to proportions never seen before, while at the same time the broad middle class grew and prospered, overall levels of inequality fell dramatically, and midsize metro areas across the South, the Midwest, and the West Coast achieved a standard of living that converged with that of America’s historically richest cites in the East. Of course, antitrust was not the only cause of the increase in regional equality, but it played a much larger role than most people realize today.

To get a flavor of how thoroughly the federal government managed competition throughout the economy in the 1960s, consider the case of Brown Shoe Co., Inc. v. United States, in which the Supreme Court blocked a merger that would have given a single distributor a mere 2 percent share of the national shoe market.

Writing for the majority, Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren explained that the Court was following a clear and long-established desire by Congress to keep many forms of business small and local: “We cannot fail to recognize Congress’ desire to promote competition through the protection of viable, small, locally owned business. Congress appreciated that occasional higher costs and prices might result from the maintenance of fragmented industries and markets. It resolved these competing considerations in favor of decentralization. We must give effect to that decision.”

In 1964, the historian and public intellectual Richard Hofstadter would observe that an “antitrust movement” no longer existed, but only because regulators were managing competition with such effectiveness that monopoly no longer appeared to be a realistic threat. “Today, anybody who knows anything about the conduct of American business,” Hofstadter observed, “knows that the managers of the large corporations do their business with one eye constantly cast over their shoulders at the antitrust division.”

In 1966, the Supreme Court blocked a merger of two supermarket chains in Los Angeles that, had they been allowed to combine, would have controlled just 7.5 percent of the local market. (Today, by contrast there are nearly 40 metro areas in the U.S where Walmart controls half or more of all grocery sales.) Writing for the majority, Justice Harry Blackmun noted the long opposition of Congress and the Court to business combinations that restrained competition “by driving out of business the small dealers and worthy men.”

During this era, other policy levers, large and small, were also pulled in the same direction—such as bank regulation, for example. Since the Great Recession, America has relearned the history of how New Deal legislation such as the Glass-Steagall Act served to contain the risks of financial contagion. Less well remembered is how New Deal-era and subsequent banking regulation long served to contain the growth of banks that were “too big to fail” by pushing power in the banking system out to the hinterland. Into the early 1990s, federal laws severely limited banks headquartered in one state from setting up branches in any other state. State and federal law fostered a dense web of small-scale community banks and locally operated thrifts and credit unions.

Meanwhile, bank mergers, along with mergers of all kinds, faced tough regulatory barriers that included close scrutiny of their effects on the social fabric and political economy of local communities. Lawmakers realized that levels of civic engagement and community trust tended to decline in towns that came under the control of outside ownership, and they resolved not to let that happen in their time.

The Rise in Per Capita Income for Selected Cities Compared to the Rise for the U.S. as a Whole

In other realms, too, federal policy during the New Deal and for several decades afterward pushed strongly to spread regional equality. For example, New Deal programs such as the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Bonneville Power Administration, and the Rural Electrification Administration dramatically improved the infrastructure of the South and West. During and after World War II, federal spending on the military and the space program also tilted heavily in the Sunbelt’s favor.

The government’s role in regulating prices and levels of service in transportation was also a huge factor in promoting regional equality. In 1952, the Interstate Commerce Commission ordered a 10-percent reduction in railroad freight rates for southern shippers, a political decision that played a substantial role in enabling the South’s economic ascent after the war. The ICC and state governments also ordered railroads to run money-losing long-distance and commuter passenger trains to ensure that far-flung towns and villages remained connected to the national economy.

Into the 1970s, the ICC also closely regulated trucking routes and prices so they did not tilt in favor of any one region. Similarly, the Civil Aeronautics Board made sure that passengers flying to and from small and midsize cities paid roughly the same price per mile as those flying to and from the largest cities. It also required airlines to offer service to less populous areas even when such routes were unprofitable.

Meanwhile, massive public investments in the interstate-highway system and other arterial roads added enormously to regional equality. First, it vastly increased the connectivity of rural areas to major population centers. Second, it facilitated the growth of reasonably priced suburban housing around high-wage metro areas such as New York and Los Angeles, thus making it much more possible than it is now for working-class people to move to or remain in those areas.

Beginning in the late 1970s, however, nearly all the policy levers that had been used to push for greater regional income equality suddenly reversed direction. The first major changes came during Jimmy Carter’s administration. Fearful of inflation, and under the spell of policy entrepreneurs such as Alfred Kahn, Carter signed the Airline Deregulation Act in 1978. This abolished the Civil Aeronautics Board, which had worked to offer rough regional parity in airfares and levels of service since 1938.

With that department gone, transcontinental service between major coastal cities became cheaper, at least initially, but service to smaller and even midsize cities in flyover America became far more expensive and infrequent. Today, average per-mile airfares for flights in and out of Memphis or Cincinnati are nearly double those for San Francisco, Los Angeles, and New York. At the same time, the number of flights to most midsize cities continues to decline; in scores of cities service has vanished altogether.

Since the quality and price of a city’s airline service is now an essential precondition for its success in retaining or attracting corporate headquarters, or, more generally, for just holding its own in the global economy, airline deregulation has become a major source of decreasing regional equality. As the airline industry consolidates under the control of just four main carriers, rate discrimination and declining service have become even more severe in all but a few favored cities that still enjoy real competition among carriers. The wholesale abandonment of publicly managed competition in the airline sector now means that corporate boards and financiers decide unilaterally, based on their own narrow business interests, what regions will have the airline service they need to compete in the global economy.

In 1980, President Carter signed legislation that similarly stripped the government of its ability to manage competition in the railroad and trucking industries. As a result, midwestern grain farmers, Texas and Gulf Coast petrochemical producers, New England paper mills, mines, and the country’s steel, automobile, and other heavy-industry manufacturers, all now typically find their economic competitiveness in the hands of a single carrier that faces no local competition and no regulatory restraints on what it charges its captive shippers. Electricity prices similarly vary widely from region to region, depending on whether local utilities are held captive by a local railroad monopoly, as is now typically the case.

The Per Capita Income of Various Regions Compared to the New York Metropolitan Area’s

Since 1980, mergers have reduced the number of major railroads from 26 to seven, with just four of these systems controlling 90 percent of the country’s rail infrastructure. Meanwhile, many cities and towns have lost access to rail transportation altogether as railroads have abandoned secondary lines and consolidated rail service in order to maximize profits.

In this era, government spending on new roads and highways also plummeted, even as the number of people and cars continued to grow strongly. One result of this, and of the continuing failure to adequately fund mass transit and high-speed rail, has been mounting traffic congestion that reduces geographic mobility, including the ability of people to move to or remain in the areas offering the highest-paying jobs.

The New York metro area is a case in point. Between 2000 and 2009, the region’s per-capita income rose from 25 percent above the average for all U.S. metro areas to 29 percent above. Yet over the same period, approximately two million more people moved away from the area to other parts of the country than moved in, according to the Census Bureau. Today, the commuter-rail system that once made it comparatively easy to live in suburban New Jersey and work in Manhattan is falling apart, and commutes from other New York suburbs, whether by road or rail, are also becoming unworkable. Increasingly, this means that only the very rich can still afford to work in Manhattan, much less live there, while increasing numbers of working- and middle-class families are moving to places such as Texas or Florida, hoping to break free of the gridlock, even though wages in Texas and Florida are much lower.

The next big policy change affecting regional equality was a vast retreat from antitrust enforcement of all kinds. The first turning point in this realm came in 1976 when Congress repealed the Miller-Tydings Act. This, combined with the repeal or rollback of other “fair trade” laws that had been in place since the 1920s and ’30s, created an opening for the emergence of large chains such as Walmart and, later, vertically integrated retail “platforms” like Amazon. The dominance of these retail goliaths has, in turn, devastated (to some, the preferred term is “disrupted”) locally owned retailers and led to large flows of money out of local economies and into the hands of distant owners.

Another turning point came in 1982, when President Ronald Reagan’s Justice Department adopted new guidelines for antitrust prosecutions. Largely informed by the work of Robert Bork, then a Yale law professor who had served as solicitor general under Richard Nixon, these guidelines explicitly ruled out any consideration of social cost, regional equity, or local control in deciding whether to block mergers or prosecute monopolies. Instead, the only criteria that could trigger antitrust enforcement would be either proven instances of collusion or combinations that would immediately bring higher prices to consumers.

This has led to the effective colonization of many once-great American cities, as the financial institutions and industrial companies that once were headquartered there have come under the control of distant corporations. Empirical studies have shown that when a city loses a major corporate headquarters in a merger, the replacement of locally based managers by “absentee” managers usually leads to lower levels of local corporate giving, civic engagement, employment, and investment, often setting in motion further regional decline. A Harvard Business School study that analyzed the community involvement of 180 companies in Boston, Cleveland, and Miami found that “[l]ocally headquartered companies do most for the community on every measure,” including having “the most active involvement by their leaders in prominent local civic and cultural organizations.”

According to another survey of the literature on how corporate consolidation affects the health of local communities, “local owners and managers … are more invested in the community personally and financially than ‘distant’ owners and managers.” In contrast, the literature survey finds, “branch firms are managed either by ‘outsiders’ with no local ties who are brought in for short-term assignments or by locals who have less ability to benefit the community because they lack sufficient autonomy or prestige or have less incentive because their professional advancement will require them to move.” The loss of social capital in many Heartland communities documented by Robert Putnam, George Packer, and many other observers is at least in part a consequence of the wave of corporate consolidations that occurred after the federal government largely abandoned traditional antitrust enforcement 30-some years ago.

Financial deregulation also contributed mightily to the growth of regional inequality. Prohibitions against interstate branching disappeared entirely by the 1990s. The first-order effect was that most midsize and even major cities saw most of their major banks bought up by larger banks headquartered somewhere else. Initially, the trend strengthened some regional-banking centers, such as Charlotte, North Carolina, even as it hollowed out local control of banking nearly everywhere else across America. But eventually, further financial deregulation, combined with enormous subsidies and bailouts for banks that had become “too big to fail,” led to the eclipse of even once strong regional money centers such as Philadelphia and St. Louis by a handful of elite cities such as New York and London, bringing the geography of modern finance full circle back to the patterns prevailing in the Gilded Age.

Meanwhile, dramatic changes in the treatment of what, in the 1980s, came to be known as “intellectual property,” combined with the general retreat from antitrust enforcement, had the effect of vastly concentrating the geographical distribution of power in the technology sector. At the start of the 1980s, federal policy remained so hostile to patent monopolies that it refused even to grant patents for software. But then came a series of Supreme Court decisions and acts of Congress that vastly expanded the scope of patents and the monopoly power granted to patent holders. In 1991, Bill Gates reflected on the change and noted in a memo to his executives at Microsoft that “[i]f people had understood how patents would be granted when most of today’s ideas were invented, and had taken out patents, the industry would be at a complete standstill today.”

These changes caused the tech industry to become much more geographically concentrated than it otherwise would have been. They did so primarily by making the tech industry much less about engineering and much more about lawyering and deal making. In 2011, spending by Apple and Google on patent lawsuits and patent purchases exceeded their spending on research and development for the first time. Meanwhile, faced with growing barriers to entry created by patent monopolies and the consolidated power of giants like Apple and Google, the business model for most new start-ups became to sell themselves as quickly as possible to one of the tech industry’s entrenched incumbents.

For both of these reasons, success in this sector now increasingly requires being physically located where large concentrations of incumbents are seeking “innovation through acquisition,” and where there are supporting phalanxes of highly specialized legal and financial wheeler-dealers. Back in the 1970s, a young entrepreneur like Bill Gates was able to grow a new high-tech firm into a Fortune 500 company in his hometown of Seattle, which at the time was little better off than Detroit and Cleveland—a depopulating, worn-out manufacturing city, labeled by The Economist as “the city of despair”—are today.

Now, a young entrepreneur as smart and ambitious as the young Gates is most likely aiming to sell his company to a high-tech goliath—or will have to settle for doing so. Sure, high-tech entrepreneurs still emerge in the hinterland, and often start promising companies there. But to succeed they need to cash out, which means that they typically need to go where they’ll be in the deal flow of patent trading and mergers and acquisition, which means an already-established hub of high-tech “innovation” like Silicon Valley, or, ironically, today’s Seattle.

They may also need to maintain a Washington office, the better to protect and expand the policies that have allowed the concentration of wealth and power in a few imperial cities, including intellectual-property protections, minimal antitrust enforcement, and financial regulations that benefit behemoth banks. The spectacular rise in the affluence of the D.C. metro area since the 1970s belies the idea that “deregulation” has brought a triumph of open and competitive markets. Instead, it is the result of a boom in what libertarians in other contexts like to call “rent seeking,” or the enrichment of a few through the manipulation of government and the cornering of markets.

Inequality, an issue politicians talked about hesitantly, if at all, a decade ago, is now a central focus of candidates in both parties. The terms of the debate, however, are about individuals and classes: the elite versus the middle, the 1 percent versus the 99 percent. That’s fair enough. But the language currently used to describe inequality doesn’t capture the way it is manifesting geographically. Growing inequality between and among regions and metro areas is obvious. But it is almost completely absent from the current political conversation. This absence would have been unfathomable to earlier generations of Americans; for most of this country’s history, equalizing opportunity among different parts of the country was at the center of politics. The resulting policies led to the greatest mass prosperity in human history. Yet somehow, about 30 years ago, America forgot its own history.