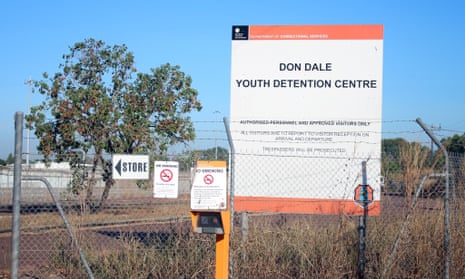

Abuse in correctional facilities underlines the enormous challenge of doing good with incarceration, particularly for very vulnerable people like children or the mentally ill. Images of abuse in the recent Four Corners report on Don Dale youth correctional facility at Darwin are gut-wrenching but sadly familiar to those who know prisons.In the United States, following revelations of abuse in New York City’s Rikers Island jail, efforts are underway to eliminate solitary confinement for youth and to close the youth facility.

Over the last few years I’ve led research teams at Harvard University, studying incarceration and its aftermath at Rikers Island, and more recently, in the Top End of the Northern Territory.

Interviewing adults in the Top End in some ways resembled the work we had been doing with formerly incarcerated men and women in the US. Incarceration goes hand in hand with poverty and violence at both ends of the planet.

In our interviews with incarcerated and formerly-incarcerated Indigenous men and women in the Northern Territory, nearly everyone we spoke to had grown up poor, insecurely housed, typically in homes wracked by family violence. Several people we talked to had been locked up at Don Dale before later being incarcerated as adults. Everyone we interviewed struggled with alcoholism or other drug abuse and alcoholism was rife in their families.

Kevin’s story was typical. He told us that his problem with drugs and alcohol began around the time his dad passed away. At 10 years old he was sniffing petrol, smoking cigarettes and marijuana at 12, and drinking at 14. He was using drugs heavily by the time he was incarcerated at Don Dale at 16.

After his release he continued to drink and use drugs, and got arrested several times, spending time in police watch houses throughout the Top End. He was drunk and high on weed and petrol when he committed his latest offence. Besides the alcohol, marijuana, and petrol, Kevin has not used other drugs. “I only drink ice with cold water,” he told us, smiling.

Although Kevin did not use ice, our interviews indicated that use of methamphetamine was common among younger people, mostly in urban areas. A stocky 26-year-old, Simon first entered Don Dale at age 13 for stealing and assault. His teenage years were spent getting arrested for fights and other “stupid kid shit.” By age 18, Simon had developed a serious addiction to methamphetamine, and by the time of his most recent incarceration, he had served nine prior prison sentences.

Michelle, in her late 30s, had just served her second prison sentence when we interviewed her. Michelle had three children, including a six month old whom she delivered while incarcerated. Michelle’s chest and arms were marked by scars. She talked to us about her two brothers now in prison and four other siblings who had passed away. She said she had had a “horrible life,” victimised by alcoholism and family violence.

Michelle was a volunteer for a program that helped elderly and disabled people but had to give up that job. She could no longer work after she was hit over the head with an iron bar and blinded in one eye in a fight between feuding factions in her family. Interviewed in a rehab program in Darwin, she didn’t want to be with her drunken family, she told us. She wanted to be with her kids.

Unlike in the US, the deep poverty that surrounds incarceration in the Northern Territory is accompanied by serious domestic violence and a profound level of alcohol abuse that engulfs entire families.

Historically, juvenile justice institutions were conceived as off-ramps from chaotic family and neighbourhood environments. The family court, with its special jurisdiction for youth under age 18, was an innovation of America’s progressive era of the early 20th century. Custodial facilities for children that were established at this time acknowledged the diminished moral responsibility of youth. The best among them featured educational and vocational programs for adolescents whose future was still in flux.

In the modern era, the neuroscience of brain development and criminological research on adolescence points to the importance of helping young people into responsible adult roles. Neuroscience shows that the adolescent brain is impulsive and cannot adequately weigh the consequences of actions. Criminological research shows that a steady job and stable family relationships are essential to diverting young people from crime.

If children have to be removed from their families for their own safety and the safety of others, custodial settings have two main tasks. First, young people need positive interactions with adults who help them improve their impulse control, judgment, future orientation and emotional maturity. Second, they need education or job training, and help in building bonds with family, in preparation for adult life after release.

Prison-like facilities are very poor instruments for the human development of young people. Because the captivity of one human being by another involves such an intense power relationship, the risks of abuse are woven into the fabric of incarceration. Transparency and oversight are necessary safeguards. Minimising incarceration, particularly for the most vulnerable, is the best approach of all.

The American experience shows that incarceration is a poor solution to violence rooted in poverty. What’s more, high levels of incarceration come with a large political cost. In majority-white societies like Australia and the US, where prison populations are mostly non-white, policymakers can become casual about the state’s awesome power to deprive liberty. When this happens, racial inequality is transformed into racial injustice. Alternatives to incarceration then become politically significant, helping to build a more inclusive citizenship in which membership in civic life is not conditional on the colour of one’s skin.

Bruce Western is a professor of sociology and a Guggenheim professor of criminal justice policy at Harvard University. His research focuses on the connections between mass incarceration and poverty and racial inequality in the US. He spent two years comparing the US experience with the Indigenous experience in the Northern Territory, Australia.