William Julius Wilson has been appointed a Nonresident Senior Fellow at Brookings. This is his first piece for us in his new capacity.

Several decades ago I spoke with a grieving mother living in one of the poorest inner-city neighborhoods on Chicago’s South Side. A stray bullet from a gang fight had killed her son, who was not a gang member. She lamented that his death was not reported in any of the Chicago newspapers or in the Chicago electronic media.

I have been thinking about that mother a good deal recently, as the Black Lives Matter movement has dramatically called attention to violent police encounters with blacks, especially young black males. Aided by smart phones and social media, Americans have now become more aware of these incidents, which very likely have occurred at similar levels in previous decades, but were “under the radar.”

This is good, of course. But it is not enough. We need to expand the focus of the movement to include groups not usually referenced when we discuss “Black Lives Matter,” including that boy in Chicago, who would by now be a grown man, perhaps with children of his own.

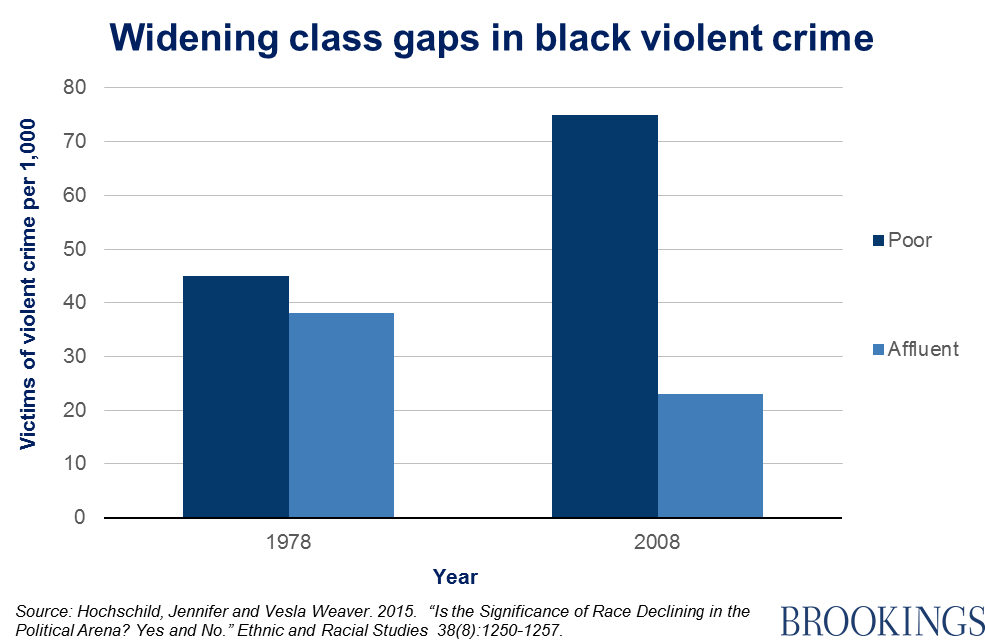

Segregation by income amplifies segregation by race, leaving low-income blacks clustered in neighborhoods that feature disadvantages along several dimensions, including exposure to violent crime. As a result, the divide within the black community has widened sharply. In 1978, poor blacks aged twelve and over were only marginally more likely than affluent blacks to be violent crime victims—around forty-five and thirty-eight per 1000 individuals respectively. However, by 2008, poor blacks were far more likely to be violent crime victims—about seventy-five per 1000—while affluent blacks were far less likely to be victims of violent crime—about twenty-three per 1000, according to Hochschild and Weaver:

Violent crime can in fact reach extraordinary levels in the poorest inner-city black neighborhoods. In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where 46 percent of African Americans live in high poverty neighborhoods—those with poverty rates of at least 40 percent—blacks are nearly 20 times more likely to get shot than whites, and nine times more likely to be murdered.

As Leon Neyfakh points out, some people are reluctant to talk about the high murder rate in cities like Milwaukee because (1) it might distract attention from the vital discussions about police violence against blacks, and (2) it runs the risk of providing ammunition to those who resist criminal justice reform efforts regarding policing and sentencing policy. These are legitimate concerns, of course.

On the other hand, it is vital to draw more attention to the low priority placed on solving the high murder rates in poor inner-city neighborhoods, reflected in the woefully inadequate resources provided to homicide detectives struggling to solve killings in those areas. As Jill Leovy, a writer at Los Angeles Times asserts in her 2014 book Ghettoside, this represents one of the great moral failings of our criminal justice system and indeed of our whole society. The thousands of poor grieving African American families whose loved ones have been killed tend to be disregarded or ignored, including by the media.

The nation’s consciousness has been raised by the repeated acts of police brutality against blacks. But the problem of public space violence—seen in the extraordinary distress, trauma and pain many poor inner-city families experience following the killing of a family member or close relative—also deserves our special attention. These losses represent another social and political imperative, described to me by sociologist Loïc Wacquant in the following terms: “The Other Side of Black Lives Matter.” They do indeed.

Commentary

The other side of Black Lives Matter

December 14, 2015