Updated | Like many New Hampshire residents—and families around the country—Ted Cruz has personal experience with addiction. As he related on the campaign trail last week and in Saturday night's debate in Manchester, the Texas senator lost his half-sister to a drug overdose. "This is a problem that, for me, I understand firsthand," Cruz told debate viewers.

He and his fellow presidential candidates are discussing addiction regularly these days—opioid addiction, specifically. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now considers it an epidemic, the result of a spike in opioid painkiller prescriptions in the 1990s that led to a nationwide surge in heroin use. The drugs are based on the same ingredient: opium. The problem is particularly intense in New Hampshire, where voters go to the polls Tuesday in the nation's first primary election. According to the CDC, the Granite State had the third-highest rate of overdose deaths of any state in 2014. Republicans and Democrats alike are eager to show voters they care. But for all their empathy, the 2016 candidates have offered few substantive solutions.

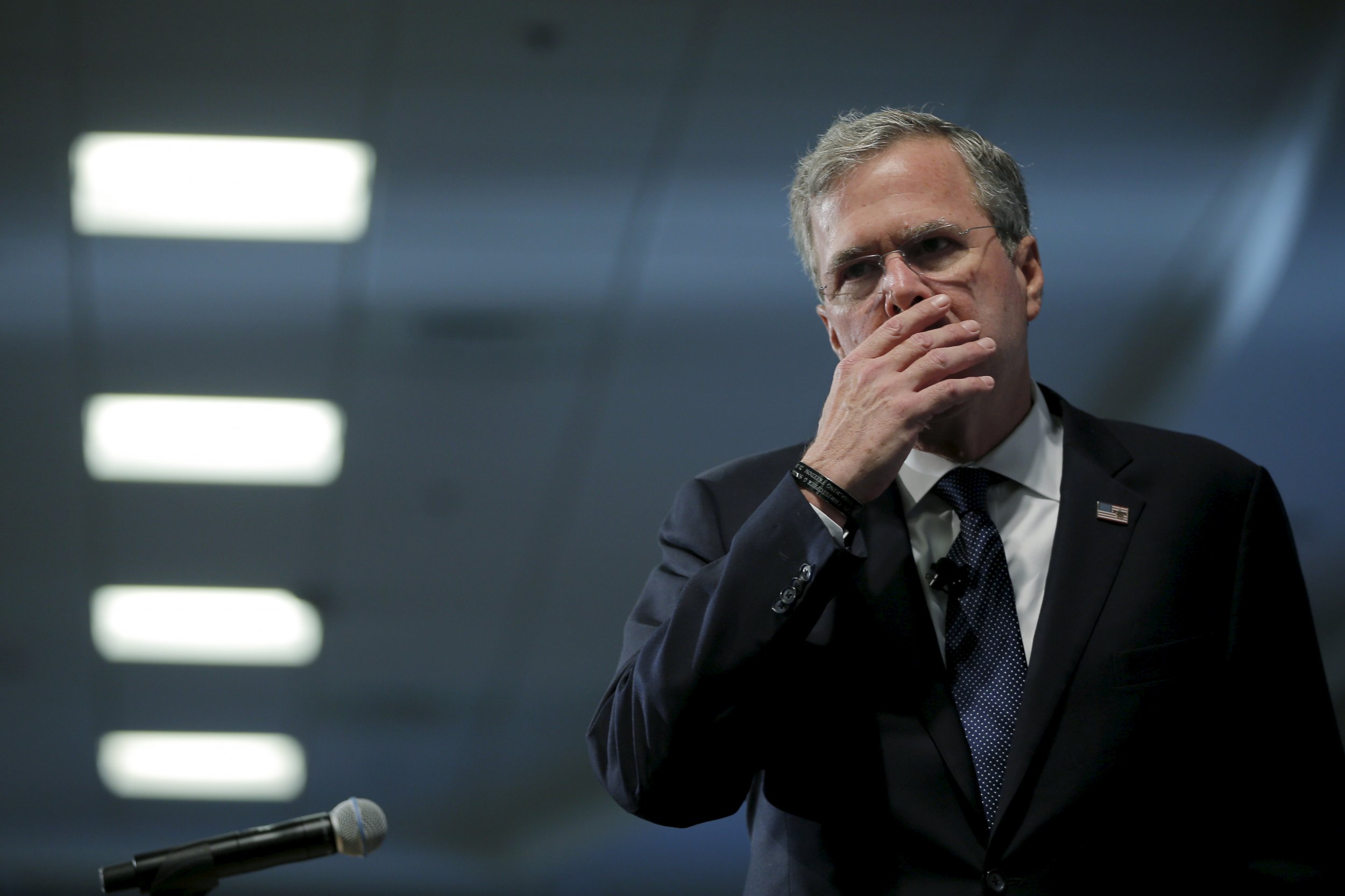

For the most part, the would-be presidents emphasize the need for state and local, as opposed to federal, responses. Of the 11 candidates, just two—former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and former Florida Governor Jeb Bush—dedicate a section of their campaign website to drug addiction. Clinton and Bush have also put out the most detailed proposals, and both have family members who publicly fought drug addiction. But even they fail to address the federal government's central role in regulating prescription drugs, which is at the root of preventing and treating opioid addiction.

The main driver of the epidemic, medical experts agree, is the overprescribing of opioid painkillers like OxyContin and hydrocodone. "Doctors have overprescribed painkillers beginning in the 1990s," says Dr. Andrew Kolodny, executive director of nonprofit advocacy group Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing. "It led to parallel increases in addiction and overdose deaths." Data compiled by the CDC show that the rise in prescriptions, opioid abuse and attending overdoses all track. How commonplace are prescribed opioids? If you watched the Super Bowl on Sunday, you might have caught an ad for a drug to treat opioid-induced constipation, of all things. That kind of pricey ad buy—reaching an audience of more than 100 million viewers—makes financial sense only if opioid use is widespread.

"Now we're trying to walk back from this medically induced harm from way too much prescribing," says Brendan Saloner, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health who has researched opioid addiction and treatment.

Kolodny blames the sudden surge in opioid prescribing on "a brilliant marketing campaign" in the 1990s by the pharmaceutical industry to convince doctors that opioids should be used not just for end-of-life pain management but also for chronic pain. If the Food and Drug Administration had been doing its job back in the late '90s, he says, it would not have allowed such marketing at all. "Even by the early 2000s, when it was very clear that the prescribing was now taking off at a level that was much greater than clinically needed," the FDA "made it easier for other drug companies" to get their own opioids approved for market, he says.

The presidential candidates rarely mention over-prescribing, however, when they talk about the scourge of drug addiction. Bush doesn't address it at all in his proposal. Clinton's plan says only that she will require prescribers "to meet requirements for a minimum amount of training, and consult a prescription drug monitoring program before writing a prescription for controlled medications."

The only candidate to single out the role of the pharmaceutical industry is Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who raised the issue in Democrats' debate in New Hampshire last week. "I think we got to talk to the pharmaceutical industry about what they're producing, doctors what they're prescribing, and then we have to make treatment available to people when they need it," Sanders said. None of the candidates ever mention the FDA.

When they talk about prevention at all, it tends to skew toward illegal drugs—the heroin coming over the border from Mexico. The one federal policy Cruz has offered to counter the opioid epidemic? "As president, I will secure the border," he proclaimed during the debate in Manchester, and "we will end this deluge of drugs that is flowing over our southern border and that is killing Americans across this country." However, in the federal government's 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 4 in 5 current heroin users reported their opioid use began with prescription painkillers. That suggests prevention needs to start with the prescriptions, not the drug cartels.

But most of the focus in the 2016 campaign and in Washington has been on treating existing addicts, as opposed to preventing new ones. Here, the federal role has largely been to provide block grants to states to help fund their programs. President Barack Obama unveiled a $1 billion initiative last week to increase treatment funding, mostly to expand access to medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorders, as well as drugs that can prevent overdoses. A bipartisan group of lawmakers has also proposed legislation focused on authorizing grants to expand local treatment and recovery programs and projects to dispose of excess painkillers. The one nod to the issue of overprescribing: It would create a task force to examine pain management best practices and opioid prescribing.

Florida Republican Marco Rubio just signed on to co-sponsor the legislation Monday, on the eve of the New Hampshire primary. "This bill will improve treatment options, increase prevention efforts, and help law enforcement fight drug abuse," he said in a statement. 2016's other two senators, Sanders and Cruz, have yet to add their names.

Sanders has, however, co-sponsored a separate bill that would lift current caps on how many patients doctors are allowed to treat with special detoxification drugs. Those caps, Saloner says, have contributed to the shortage in treatment slots.

As it stands now, the Controlled Substances Act restricts physicians "to at most 100 patients they can provide buprenorphine"—one of two drugs used to manage opioid cravings—says Saloner. There's an irony, he notes, to the fact that doctors are required to get a special permission from the Drug Enforcement Administration to prescribe such drugs, yet "you don't need any special permission to prescribe opioids." The federal government and Congress, in particular, have the power to change that. The presidential candidates have been silent on the matter.

Insurance coverage is another issue. "We lose more people because of insurance companies that don't cover opiate detox," says Melissa Crews, chairwoman of the board at Hope for New Hampshire Recovery, a peer-to-peer recovery support center based in Manchester.

Crews and other experts say the grants and funding that the White House and other federal policymakers have focused on are needed. Though states and local communities are starting to ramp up their responses, the resources available don't match the need, they say. Saloner co-authored a paper published last year that found 80 percent of people abusing opioids did not receive any treatment between 2004 and 2013. In the Granite State, Hope for New Hampshire was the first recovery center to open, just this July.

The center has hosted four presidential candidates in recent months—Bush, Sanders, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie and former Hewlett-Packard CEO Carly Fiorina, who just held an event there over the weekend. Bush, Christie and Fiorina have all spoken in personal terms about loved ones' struggles with drug abuse. Crews echoes many of the candidates when she emphasizes the need for flexible, local solutions. But she also sees a role for the federal government. "I would love to see more guidelines for recovery support services," in addition to clinical treatment, she says.

And even if the 2016 candidates haven't offered clear fixes for the crisis, people like Crews and Saloner are pleased they are talking about the problem of opioid addiction with compassion. There's "a desire to talk about it in a way that's not stigmatizing or criminalizing, which is very important," says Saloner. That's a shift, he notes, from a decade ago, when the news that Bush's daughter had a drug problem was considered a scandal. Crews agrees. She's cheered by the fact that people affected by addiction have been speaking up at New Hampshire's town halls as the election approaches. "They say, 'I'm not ashamed to talk about this anymore.'"

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the first name of Brendan Saloner.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Emily spearheads Newsweek's day-to-day coverage of politics from Washington, D.C. She has been covering U.S. politics, Congress and foreign affairs ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.