After news broke that a group of Milwaukee police officers savagely beat an unarmed black man named Frank Jude in 2004, the city saw crime-related 911 calls drop by about 20 percent for more than a year—totaling about 22,200 lost reports of crimes—according to a new study by a group of sociologists at Harvard, Yale, and Oxford universities.

The outcome wasn’t unique to Jude’s beating, the researchers found. Looking at the city's 911 call records from 2004 to 2010, they noted similar drops after other highly publicized local and national cases of police violence against unarmed black men.

The findings square with earlier research showing that communities—specifically black communities given recent events—become more cynical of law enforcement after brutality cases. But the new study, published in the October issue of the American Sociological Review, is the first to show that people actually change their behavior based on that elevated distrust. Namely, community members become less likely to report crimes to law enforcement, likely out of fear of interacting with police or skepticism that police will take them seriously and help.

This, in turn, may contribute to crime spikes. In the six months after local media first reported Jude’s beating in February of 2005, homicides surged by 32 percent over the previous six months. The researchers noted it was the city’s deadliest period across the seven years they studied.

“Police departments and city politicians often frame a publicized case of police violence against an unarmed black man as an ‘isolated incident,’” the authors noted. However, “the findings of this study promote a more sociological view of the issue by suggesting that no act of police violence is an isolated incident, in both cause and consequence.”

The drop in 911 calls also cast doubt on another common theory: that crime levels rise following such brutality cases because communities lash out and police become afraid to use force. But reluctance to use force is irrelevant if police aren’t responding to crimes. Instead, it’s the fears of the community members that seem to make a difference, the researchers suggest.

Frank Jude’s beating

The researchers, led by Matthew Desmond of Harvard, chose to analyze 911 call records around Jude’s beating because it was one of the city’s most publicized cases and was also shockingly brutal. According to news reports and court documents, on October 23, 2004, Jude and his friend, Lovell Harris (both black), accompanied two women to the house-warming party of Milwaukee police officer Andrew Spengler. Jude and Harris quickly became uncomfortable in the company of Spengler and his officer friends, who were largely white. They decided to leave. But as the four were pulling away from the house in their truck, a group of at least 10 officers surrounded them and accused Jude of stealing Spengler’s police badge. The officers pulled the four from the truck and began assaulting Jude and Harris and used racial slurs. After Harris had his face slit with a knife, he ran and escaped. Jude however, didn’t. As summarized by Desmond in the study (warning: the following includes graphic detail):

Spengler and several other off-duty police officers began beating Jude about the face and torso while another pinned his arms behind his back. When Jude collapsed to the ground, the officers kicked his head. A pair of on-duty officers arrived around 3:00 a.m. (Jude’s female companions had called 911 before partygoers seized their phones.) One uniformed officer, Joseph Schabel, stomped on Jude’s face until he heard bones breaking. The other on-duty officer watched. An off-duty officer picked Jude up and kicked him in the crotch with such force his feet left the ground. Another took one of Schabel’s pens and pressed it deep into Jude’s ear canals. Another bent Jude’s fingers back until they snapped. Spengler put a gun to Jude’s head. Jude was left naked from the waist down lying on the street in a pool of his own blood.

When more on-duty officers arrived, Jude was taken to the hospital. In addition to bruises, broken bones, and cuts all over his body, his left eye bled for 10 days. He also suffered permanent damage in one hand, vision problems, as well as night terrors and PTSD. Meanwhile, all of the officers continued working and refused to cooperate with an internal investigation into the incident. Spengler’s badge was never found and Jude was never charged.

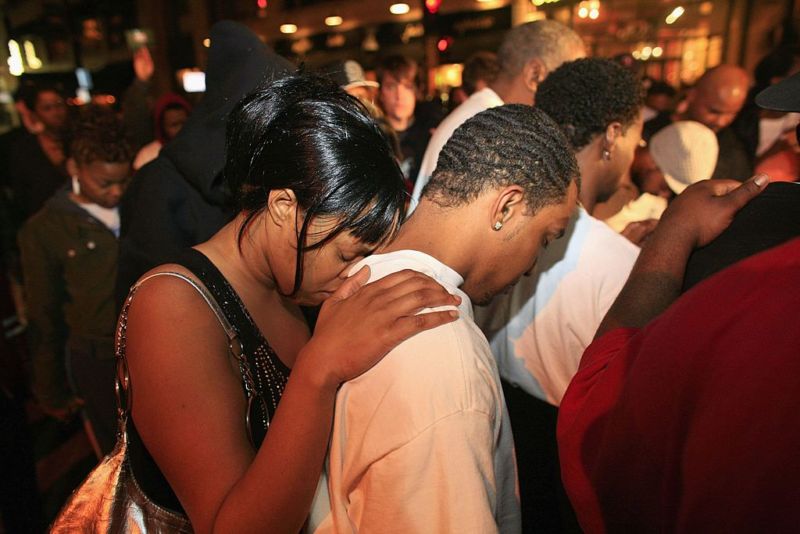

The public wasn’t aware of the gruesome beating until February 6, 2005, when the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel published a Sunday article accompanied by a photo of Jude’s bloodied face. Community protests broke out. A month later, nine officers were fired and four were disciplined. Spengler and two other officers were initially tried and acquitted by all-white juries in a state court. However, eight were later charged in federal court and seven were found guilty. Spengler and two others are now serving prison terms of 15 to 17 years.

Dropped calls

Desmond and his team collected the 911 records from March of 2004—more than six months prior to Jude’s beating—to December 2010. The period encompassed more than a million calls. After sorting out the ones that weren’t related to crime (medical emergencies, automated alarms, car accidents, and fires), the researchers were left with 883,146. They controlled for neighborhood characteristics, crime rates, and call patterns in their subsequent analysis.

At the time of the beating, the researchers saw no change in 911 calls, suggesting that word-of-mouth of Jude's case was not strong enough to make a noticeable impact. However, directly after the Sentinel’s article in February, the researchers noted a significant drop in calls. Although call rates gradually recovered, it took a year to do so—and even longer in black communities. In total, the researchers estimate that about 22,200 calls were lost. About 56 percent of those calls would have come from black neighborhoods.

The researchers noted similar declines after news broke of the 2006 assault of 19-year-old Danyall Simpson by a white officer in Milwaukee and the killing of unarmed Sean Bell by white officers in Queens, New York in 2006 on Bell's wedding day.

As a control, the researchers found no such drops in 911 calls related to car accidents, which are often required for insurance purposes, during the relevant time frames.

“Police misconduct can powerfully suppress one of the most basic forms of civic engagement: calling 911 for matters of personal and public safety,” the authors concluded.

American Sociological Review, 2016. DOI: 10.1177/0003122416663494 (About DOIs).

reader comments

228