Even in the most desolate areas of American cities, evictions used to be rare enough to draw crowds. Eviction riots erupted during the Depression, even though the number of poor families who faced eviction each year was a fraction of what it is today. A New York Times account of community resistance to the eviction of three Bronx families in February 1932 observed: “Probably because of the cold, the crowd numbered only 1,000.” Sometimes neighbours confronted the marshals directly, sitting on the evicted family’s furniture to prevent its removal or moving the family back in despite the judge’s orders. The marshals themselves were ambivalent about carrying out evictions. It wasn’t why they carried a badge and a gun.

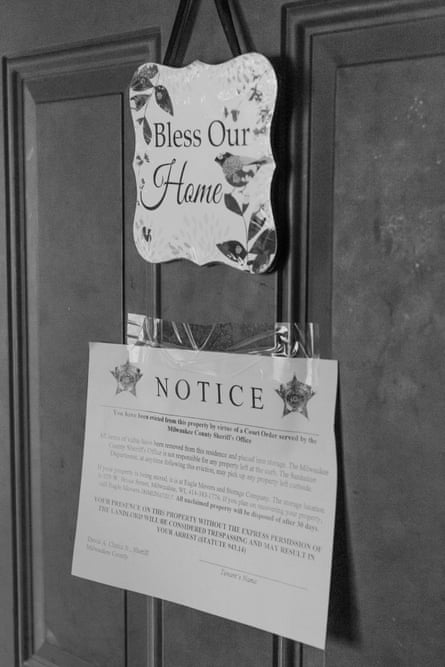

These days, there are sheriff squads whose full-time job is to carry out eviction and foreclosure orders. There are moving companies specialising in evictions, their crews working all day, every weekday. There are hundreds of data-mining companies that sell landlords tenant-screening reports listing past evictions and court filings. These days, housing courts swell, forcing commissioners to settle cases in hallways or makeshift offices crammed with old desks and broken file cabinets – and most tenants don’t even show up. Low-income families have grown used to the rumble of moving trucks, the early morning knocks at the door, the belongings lining the kerb.

In America, families have watched their incomes stagnate, or even fall, while their housing costs have soared. Median rent has increased by more than 70% since 1995. Meanwhile, only one in four families who qualify for housing assistance receive it, and in the nation’s biggest cities the waiting list for public housing is not counted in years but decades. The typical poor American family does not live in public housing but receives no government assistance whatsoever. The result? Today, the majority of poor renting families in America spend more than half of their income on housing, and at least one in four dedicates more than 70% to paying the rent and keeping the lights on.

It is estimated that millions of Americans are evicted every year because they can’t make rent. In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a city of fewer than 105,000 renter households, landlords evict roughly 16,000 adults and children each year. That’s 16 families evicted through the court system daily. New York City sees 60 marshal evictions a day. The most recent version of the American Housing Survey asked people: “Do you think you’ll be evicted soon?” Renters in more than 2.8m homes said yes.

A landlord can evict tenants through a formal, court process. But there are other ways, cheaper and quicker ways, to remove a family. Some landlords pay tenants a couple of hundred dollars to leave by the end of the week. Some take off the front door. Nearly half of all forced moves experienced by renting families in Milwaukee are “informal evictions” that take place in the shadow of the law. If you count all forms of involuntary displacement – formal and informal evictions, landlord foreclosures, building condemnations – you discover that between 2009 and 2011 more than one in eight Milwaukee renters experienced a forced move. That is a shockingly high amount of residential insecurity.

The face of America’s eviction epidemic belongs to mothers with children. Until recently, the housing court in New York City’s South Bronx had a daycare facility inside it because there were so many children coming through its doors.

Eviction’s fallout is severe. Losing a home sends families to shelters, abandoned houses, and the street. It invites depression and illness, compels families to move into degrading housing in dangerous neighbourhoods, uproots communities, and harms children. Eviction is not merely a condition of poverty; it is a cause of it too.

Since the publication of Evicted, I have had countless conversations with concerned families across America. Teachers in under-served communities have told me about high classroom turnover rates, which hinder students’ ability to reach their full potential. Public-sector union organisers have told me about how firefighters, police officers, and nurses can no longer afford to live in the cities they serve and protect. Healthcare providers have helped me see that decent, safe housing can promote physical and mental wellness; and engaged citizens have shown me the civic potential of stable, vibrant blocks where neighbours know one another by name.

But eviction can erase all that, destabilising families, schools and entire communities. The lack of access to affordable, decent housing sits at the root of so many of America’s social ills. Without stable shelter, everything else falls apart. This means it is impossible to address poverty in America without fixing housing.

This is also not only America’s problem. In the United Kingdom, the cost of an average house requires 10 years of the average British salary; the average London house requires double that. Rents in Delhi’s business district now rival those in midtown Manhattan. Between 2008 and 2014, housing prices in São Paulo increased by more than 200%.

Over the past several decades, millions of people have migrated to cities from rural villages and towns. In 1960, roughly a third of the planet lived in urban areas; today, more than half does. Cities have experienced real income gains that have brought about global poverty reductions. But therein lies the rub, as the growth of cities has also been accompanied by an astonishing surge in land values and housing costs, especially in “superstar cities” whose real-estate markets have experienced an influx of global capital. Roughly 330m urban households worldwide live in substandard or unaffordable housing demanding more than 30% of their income. By 2025, based on migration trends and global income projections, that number is expected to climb to 440m households, representing 1.6 billion people. The world is becoming urbanised, and cities are becoming unaffordable to millions everywhere.

The two great global threats of our time are climate change and unlivable cities. Let’s get to work.

*****

Larraine’s trailer was spotless and uncluttered. When a visitor commented on its cleanliness, she would smile and credit her handheld steamer or share tips, like slipping in an aspirin when washing whites. She had lived in her trailer for about a year and had come to like it, especially in the morning, before the gossips began congregating outside. She now had everything just-so. She had found white serving utensils to match the white cupboards in the kitchen and a small desk for her old computer. None of this made paying Tobin [owner of the trailer park] 77% of her income any easier.

Larraine studied her phone, dialling a number by heart. “Yes. I was wondering. I was told that you help people with their rent?… Oh. Oh, no?… OK.” She hung up. Larraine dialled the Social Development Commission, an anti-poverty organisation. They couldn’t help. Someone had told her that the YMCA on 27th made emergency loans. She called them. “Yes. I was instructed to call you because I was told you could help me with my rent… My rent… Rent. R-E-N-T.” By mid-morning, Larraine had dialled all the nonprofit, city, and state agencies she could think of. None came through.

*****

The movers started the trucks early in the morning, diesel engines grumbling as the men gathered with cigarettes and mugs of black coffee. The city was soggy from the previous night’s rain. Some of the men were young and athletic with pierced ears. Others were barrel-chested and middle-aged, slapping their leather gloves on their jeans. The oldest among them was Tim, lean and sour-faced with reddish-brown skin, stubble, and a fresh pack of Salems in his front pocket. Almost all of the men were black and wore boots and work jackets with the name of their company – Eagle Moving and Storage – and various clever slogans: “Moving’s for the birds”, “Service with a grunt”, “Order some carryout”.

The Brittain brothers – Tom, Dave and Jim – had taken over the company from their father. When he had started it back in 1958, there were only one or two eviction moves a week. He ran a two-truck operation out of his home and would pick up men from the rescue mission when he needed an extra hand. Fifty years later, the company employed 35 people, most of them full-time movers, owned a fleet of vans and 18ft trucks, and operated out of a three-storey building that had originally held a furniture factory. In total, 40% of their business came from eviction moves.

Eagle’s moving crew worked with two sheriff deputies. The deputies would knock on the door to announce the eviction; the movers would follow, clearing out the home. Landlords footed the bill. A formal eviction that involved sheriffs and movers could run to about $600 (£482), when you included the court filing charge and process-server fee. Landlords could add these costs to a judgment but often never got them back.

Dave Brittain, a white man with greying hair and a long stride, gave the men the signal, and they climbed into the trucks.

The sheriffs met the moving crew outside an apartment complex on Silver Spring Drive. John, the older of the two deputies and the one who most looked the part – broad shoulders, thick jowls, sunglasses, cop moustache, gum – gave the door a knock. A small black woman answered, rubbing the sleep out of her eyes. When John looked around and saw a tidy house with dishes drying in the rack and not a box packed, he turned to his partner and asked, “Are we in the right house?” He placed a call back to the office.

When Sheriff John walked into a house and saw mattresses on the floor, grease on the ceiling, cockroaches on the walls, and clothes, hair extensions, and toys scattered about, he didn’t double-check. Sometimes tenants had already abandoned the place, leaving behind dead animals and rotting food. Sometimes the movers puked. “The first rule of evictions,” Sheriff John liked to say, “is never open the fridge.” When things were especially bad, when an apartment was covered in trash or dog shit, or when one of the guys found a needle, Dave would nod and say, “Junk in”, leaving the mess for the landlord.

John hung up the phone and waved the movers in. At that moment, the house no longer belonged to the occupants, and the movers took it over. Grabbing dollies, hump straps, and boxes, the men began clearing every room. They worked quickly and without hesitation. There were no children in the house that morning, but there were toys and diapers. The woman who answered the door moved slowly, looking overcome. A sob broke through her blank face when she opened the refrigerator and saw that the movers had cleaned it out, even packing the ice trays. She found her things piled in the back alley. Sheriff John looked to the sky as it began to rain and then looked back at Tim. “Snowstorm. Rainstorm. We don’t give a shit,” Tim said, lighting a Salem.

*****

Larraine had grown up with two brothers and two sisters in a squat, yellow-brick public housing complex across the street from a baseball field in south Milwaukee. Her mother was an invalid, her body swollen on account of her thyroid. Her father was a window washer. Larraine remembered him bringing home bags of Ziegler Giant Bars when he washed the windows of the candy factory, or armloads of fresh bread when the day’s schedule took him to certain local restaurants. Larraine loved her childhood, especially her doting father. “We didn’t know we were poor,” she said.

Larraine had struggled in school. In 10th grade, she decided she’d had enough. “Everyone around me was making it but me.” She dropped out and began working as a seamstress for $1.50 an hour. She went to work at Everbrite, which manufactured corporate signs. During a strike, she left and found work as a machinist at R-W Enterprises on Sherman Avenue. Her father constantly worried about his young daughter working with sheet metal and operating punch press machines. Maybe that’s why, when a metal disc came down on her hand one day and pinched off the top half of her two middle fingers, all she remembered doing was crying out for her daddy.

At 22, Larraine married a man named Jerry Lee. They had a daughter three years later, and another two years after that. But soon the marriage began to unwind. It got to the point where Jerry Lee began bringing women back to their home. They divorced after eight years, and Larraine began life as a single mother. Those years were filled with poverty and double shifts and freedom and laughter. If you asked Larraine, she would tell you they were some of the best years of her life. She would bring the girls to her day job cleaning houses. They’d pitch in, and Larraine would split her pay cheque.

*****

The Eagle Moving trucks stopped outside a north-side duplex with cream siding. An older child answered the door: a girl, maybe 17, with shorn hair, dark-brown skin and unflinching grey eyes.

Dave and the crew hung back, waiting for John to give the OK. The deputies always went first and absorbed tenants’ blowback if there was any. Things often got loud; they rarely got violent. Sheriffs used different diffusion strategies. John preferred meeting aggression with aggression. Once, he called the sheriff’s office in front of a woman in a bathrobe and headwrap, saying into the phone, “If she doesn’t shut her mouth and start talking like an adult, I’m going to throw her shit in the street!” The conversation with Grey Eyes was taking longer than usual. Dave watched a white man in a flannel shirt park his truck and approach the door. Landlord, he figured. After a few more minutes, John nodded at Dave, and the crew sprang up.

Inside the house, the movers found five children. Tim recognised one child as the daughter of a man who used to work on the crew. It wasn’t uncommon to evict someone you knew. Most of the movers lived on the north side and had at some point experienced the awkward moment of packing up someone from their church or block. Tim had evicted his own daughter. But this house felt strange. Dave asked what was going on, and John explained that the name on the eviction order belonged to the mother of several of the children. She had died two months earlier, and the children had simply gone on living in the house, by themselves.

As the movers swept through the rooms, Grey Eyes took charge, giving orders to the other children; the youngest was a boy of about eight or nine. Upstairs, the movers found ratty mattresses on the floor and empty liquor bottles displayed like trophies. In the damp basement, clothes were flung everywhere. The house and the yard were littered with trash. “Disgusting,” Tim said of the roaches scaling the kitchen wall.

As the landlord changed the locks with a power drill and the movers pushed the contents of the house on to the wet kerb, the children began to run around and laugh.

When the move was done, the crew gathered by the trucks, instinctively stomping the ground to shake loose any stowaway roaches. Those who smoked reached for their packs. They didn’t know where the children would go, and they didn’t ask.

With this job, you saw things. The guy with 10,000 audio cassette tapes of UFO activity who kept yelling, “Everything is in order! Everything is in order!” The woman with jars full of urine. The guy who lived in the basement while his pack of chihuahuas overran the house. Just a week earlier, a man had told Sheriff John to give him a minute. Then he shut the door and shot himself in the head. But the squalor was what got under your skin; its smells and sights were what you tried to drink away after your shift.

Grey Eyes leaned against the porch rail and took long drags of her own cigarette.

*****

Larraine considered asking her brothers and sisters for help. There was her eldest sister, Odessa, who lived a few miles away and spent her days in a nightgown on a corduroy recliner, watching talk shows next to a lampstand crowded with prescription medication containers. She was on supplemental security income, and wouldn’t be able to help even if she were willing, which she wasn’t. Beaker was in worse shape than Odessa. A towering man with loose skin, Beaker was 65 and a heavy smoker who relied on a walker. The family, in the midwestern way, liked to poke fun at his failing health. “We’ve got the funeral home on speed dial!” Even if he wasn’t in the hospital, Beaker’s social security stipend was even less than Larraine’s. He could afford the rent but little else, living hard in a filthy trailer covered in clothes, cigarette boxes and butts, food-encrusted plates, and stray dog shit.

Then there was Ruben, the blessed child. He was the only one who hadn’t inherited their father’s Croatian nose. And he didn’t live in the trailer park, or even a trailer park, or even in Cudahy, like Odessa. He lived in Oak Creek, in his own home, which was big enough to host everyone for Thanksgiving dinner every year. Larraine could ask Ruben for the rent money, but she wasn’t close with her baby brother. Plus, asking for help from better-off kin was complicated. Those ties were banked, saved for emergency situations or opportunities to get ahead. People were careful not to overdraw their account because when family members with money grew exhausted by repeated requests, they sometimes withheld support for long periods of time, pegging their relatives’ misfortunes to individual failings. This was one reason why family members in the best position to help were often not asked to do so.

Larraine thought her best bet was to approach her younger daughter, Jayme. Larraine found a ride to Arby’s [restaurant], where Jayme worked. Jayme looked up from a pile of dirty dishes, rolled her eyes at her mother, and came walking to the front, her thick auburn curls tucked beneath an Arby’s hat. She was not much taller than Larraine and wore wire glasses and a nun’s expression: warm but distant. Jayme whispered, “Mom, you’re not supposed to be here.” “I know,” Larraine said, dropping her smile to look deeply sad. “I know, honey. But I just got a 24-hour eviction notice. They are going to throw me out if I don’t pay the rent. And, um, I was wondering if there was any way you could help me?”

“I can’t.”

“OK.”

“I can’t.”

Larraine gathered herself in the Arby’s parking lot. Office Susie had told her to ask her family for rent. She often heard a similar line at the crisis centres. When the social workers behind the glass asked her, “Well, don’t you have family that can help?” Larraine sometimes would reply, “Yes, I have family, and, no, they can’t help.”

*****

At the next house, a Hispanic woman in her early 40s answered the door holding a wooden spoon.

“Can I have until Wednesday?” she asked.

The deputies shook their heads: no. She nodded with forced resolve or submission.

Dave stepped on to the porch. “Ma’am,” he said, “we can place your things in our truck or on the kerb. Which would you prefer?” She opted for the kerb. “Kerbside service, baby!” Dave hollered back to the crew.

Dave stepped into the house and tripped over a Dora the Explorer chair. He reached over an older man sitting at the table and flipped on more lights. The house was warm and smelled of garlic and spices. One of the deputies pointed to the built-in cabinets in the kitchen. “This is the kind of shit I like,” he told his partner. “They don’t make this stuff any more. Tight.”

The woman walked in circles, trying to think where to begin. She told one of the deputies that she knew she was being foreclosed but that she didn’t know when they were coming. Her attorney had told her that it could be a day, five days, a week, three weeks; she decided to ride it out. She and her three children had been in the house for five years. The year before, she had been talked into refinancing with a sub-prime loan. Her payments kept going up, jumping from $920 to $1,250 a month, and her hours at Potawatomi casino were cut back after her maternity leave.

Hispanic and African American neighbourhoods had been targeted by the sub-prime lending industry: renters were lured into buying bad mortgages, and homeowners were encouraged to refinance under riskier terms. Then it all came crashing down. Between 2007 and 2010, the average white family experienced an 11% reduction in wealth, but the average black family lost 31% of its wealth. The average Hispanic family lost 44.7%.

A mover started in on a girl’s bedroom, painted pink with a sign on the door announcing: “The princess sleeps here.” Another took on the dishevelled office, packing Resumés for Dummies into a box with a chalkboard counting down the remaining days of school. The eldest child, a seventh-grade boy, tried to help by taking out the trash. His younger sister, the princess, held her two-year-old sister’s hand on the porch. Upstairs, the movers were trying not to step on the toddler’s toys, which when kicked would protest with beeping sounds and flashing lights.

As the move went on, the woman slowed down. At first, she had borne down on the emergency with focus and energy, almost running through the house with one hand grabbing something and the other holding up the phone. Now she was wandering through the halls aimlessly, almost drunkenly. Her face had that look. The movers and the deputies knew it well. It was the look of someone realising that her family would be homeless in a matter of hours. It was something like denial giving way to the surrealism of the scene: the speed and violence of it all; sheriffs leaning against your wall, hands resting on holsters; all these strangers, these sweating men, piling your things outside, drinking water from your sink poured into your cups, using your bathroom. It was the look of being undone by a wave of questions. What do I need for tonight, for this week? Who should I call? Where is the medication? Where will we go? It was the face of a mother who climbs out of the cellar to find the tornado has levelled the house.

*****

Larraine answered a knock at her door and found two sheriff deputies standing on her small porch. Behind them, the Eagle Moving trucks were pulling into the trailer park. It was a tight pinch for the drivers, manoeuvring through the narrow entrance, minding the unleashed dogs and children, and backing up to the designated spot; but Eagle had been in Tobin’s park plenty of times. It was the last move of the day, and the crew was sore and eager to get home. The movers were hoping for a “junk in”, but Larraine asked that her things be taken to storage. The movers began filling boxes with Larraine’s things: the white utensils in the kitchen, a Christmas gift for her grandson.

Larraine stood outside, silently looking on. The movers carried out her chair, her washing machine, her refrigerator, stove, dining table. Next came the boxes with who knows what inside: perhaps winter jackets or shoes or shampoo. The neighbours began to gather. Some grabbed beers and positioned lawn chairs as if watching a Nascar race.

It didn’t take long. Larraine was cleaned out in less than an hour. She watched the truck lurch away. Her things were headed to Eagle’s storage warehouse, a dimly lit expanse with clear lightbulbs strung from a ceiling supported by large wooden pillars. Inside, there were hundreds upon hundreds of piles, each representing an eviction or foreclosure. The piles were stacked to eye level and individually encircled in shrink-wrap like so many silken-wound insects on a spider’s web. Up close, the contents were visible through the taut clear wrapping: scratched-up furniture, lamps, bathroom scales, and everywhere children’s things – rocking horses, strollers, baby swings, bouncy seats. The Brittain brothers thought of the warehouse as a “giant stomach”, digesting the city. They charged $25 per pallet per month. The average evicted family’s possessions took up four pallets, or 400 cubic feet.

Larraine would have to find a way to pay her storage bill. If she fell 90 days behind, Eagle would get rid of her pile to make room for a new one. This was the fate of roughly 70% of lots confiscated in evictions or foreclosures. Most of the stuff ended up in the dump.

Larraine dragged herself to her brother’s trailer. She swallowed pain pills, including 200mg of Lyrica. In silence, she let the painkillers work. Once they had, she looked around, let out a muffled scream, and began punching the couch over and over and over again.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion